Quiet, smooth and powerful, the Classic Era V16 engines built in the 1930s by Cadillac in Detroit and by Marmon in Indianapolis remain landmarks of automotive history. These top-of-the-line powerplants inspired coachbuilders to work to their highest standards for a discerning clientele that had somehow managed to remain wealthy through the depths of the Great Depression.

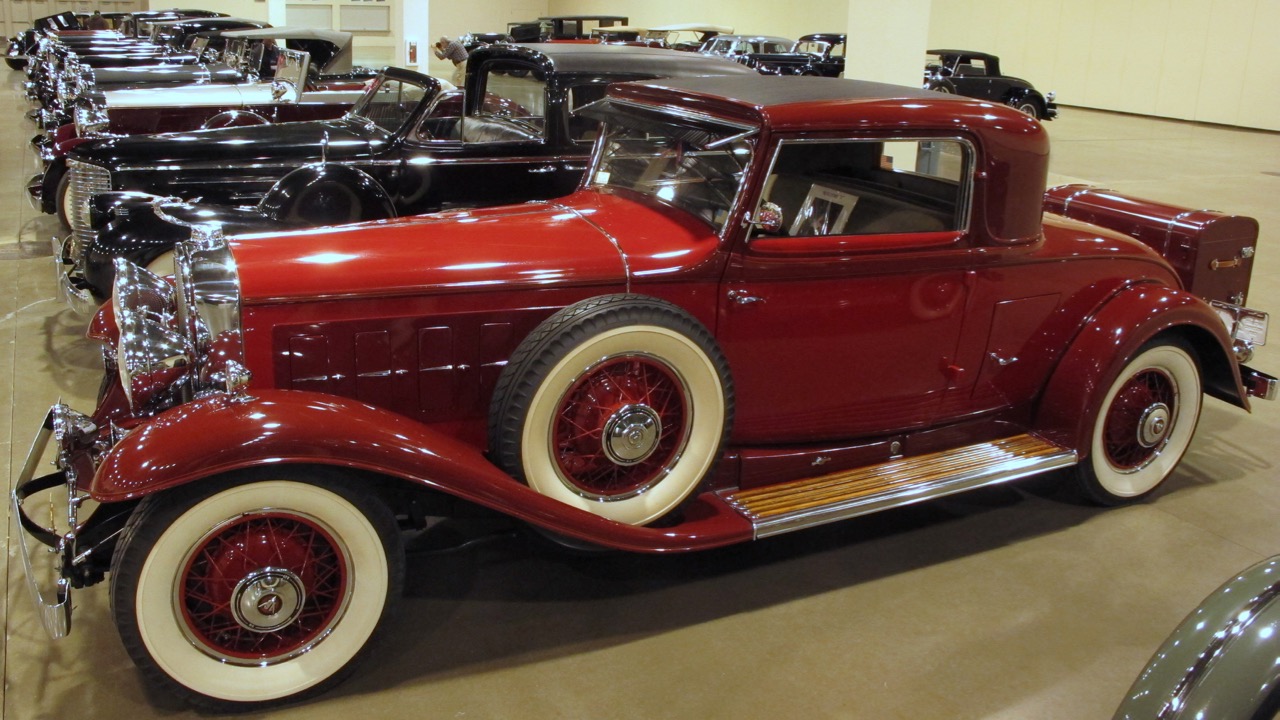

Twenty examples including the single Peerless V16 prototype — the only such car built by a domestic automaker other than Cadillac or Marmon — gathered last week for an exhibit dubbed Sweet Sixteens. It was part of the judged car show accompanying the 2016 annual meeting of the Classic Car Club of America, this year in the Detroit suburb of Novi and coincident with the opening weekend of the North American International Auto Show.

CCCA publicity prior to the meet said the aim was put together the largest gathering of V16 cars, ever. Twenty is a good turnout, but it seems likely that the number has been or will be exceeded at one of the nation’s premier concours. If there was a weakness in the gathering, it was a shortage of the later-era 1938-1940 Cadillacs reflective of Harley Earl’s rising Styling department at GM.

First, a brief history of the V16: In 1925, Lawrence Fisher was named head of GM’s Cadillac Division (the company had acquired controlling interest of the previously independent marque in 1919 and owned it entirely by 1926). Fisher hired engineer Owen Nacker away from Marmon and put him in charge of engines.

Several sources say Nacker had previously discussed the idea of a V16 engine with Howard Marmon, but the smaller firm didn’t have the capital resources to develop it as rapidly as GM could do when Fisher decided a V16 would be just the thing to put his company on par with Pierce-Arrow, Packard and Peerless (the high-priced three “P”s of the 1920s). Cadillac’s top engine at the time was a V8 and while many anticipated it was preparing a V12, the V16 took priority instead and rolled out first for 1930 models, right on the heels of the stock market crash of 1929. The twelve came a year later.

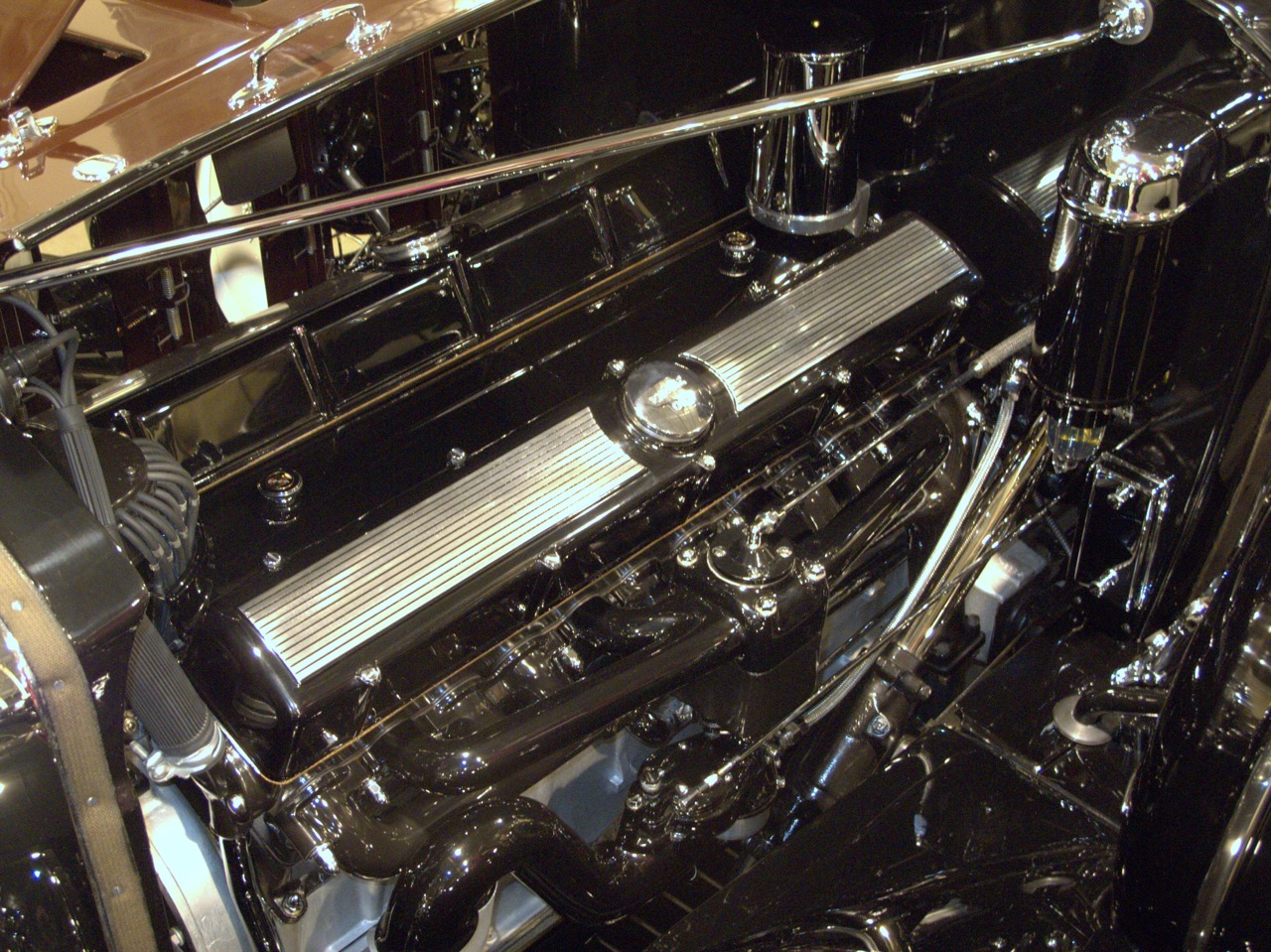

The V16 was essentially a pair of straight 8s mounted at a 45-degree angle atop a common crankcase. With a 3-inch bore and 4-inch stroke it displaced 452 cubic inches — the company would make V8s that big in the ‘60s, but it was significantly larger than competitor’s engines. It also had overhead valves when Cadillac’s V8 was still a flathead. This first-generation V16, known as the Series 452, mounted its intake and exhaust manifolds both on the outside of the cylinder heads and was officially and conservatively rated at 165 horsepower, later bumped to 185, or roughly twice the V8’s 90-hp peak. Dynamometer tests showed 320 lb-ft at 1200 rpm — with 16 modestly sized cylinders, it was ultra-smooth and could cruise happily in top gear at near-idle speeds.

Marmon first showed its own V16 only 11 months after Cadillac in terms of first public exhibition but there was nearly two years gap between them in terms of full production and on-sale date.

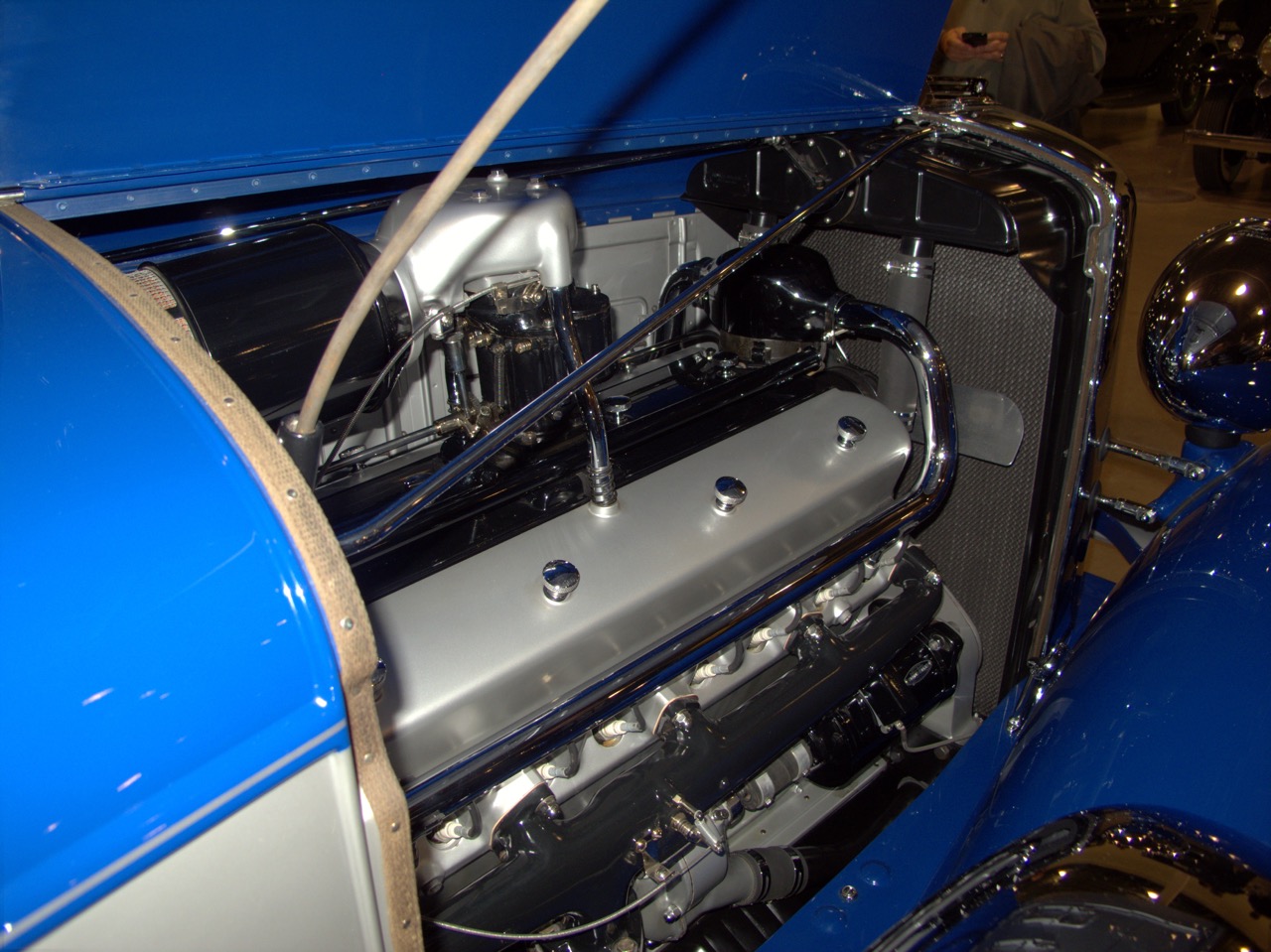

The Marmon was arguably a superior engineering achievement, though. Displacing 500 cubic inches and claiming 200 horsepower, the car tested 10 mph faster than a contemporary Cadillac V16. Marmon, too, had an included angle between the banks of 45- egrees, but the block was an aluminum casting (with iron cylinder liners) and so were the heads. So Marmon’s Sixteen was not only more powerful, it weighed 930 pounds vs. Cadillac’s beast, which reportedly weighed 1,300 pounds with all accessories. Marmon mounted its intake manifold (with only one giant carburetor) between the banks for better flow through the heads.

GM had the superior marketing system, however, and imagine yourself a well-heeled buyer in 1932, watching small companies going bankrupt left and right, trying to decide whether to buy from the Detroit behemoth or the little guy with better ideas who’d won the Indianapolis 500 twenty years earlier. The V16 was Marmon’s last gasp, the last model in its catalog and fewer than 400 had been built before the company folded in 1934.

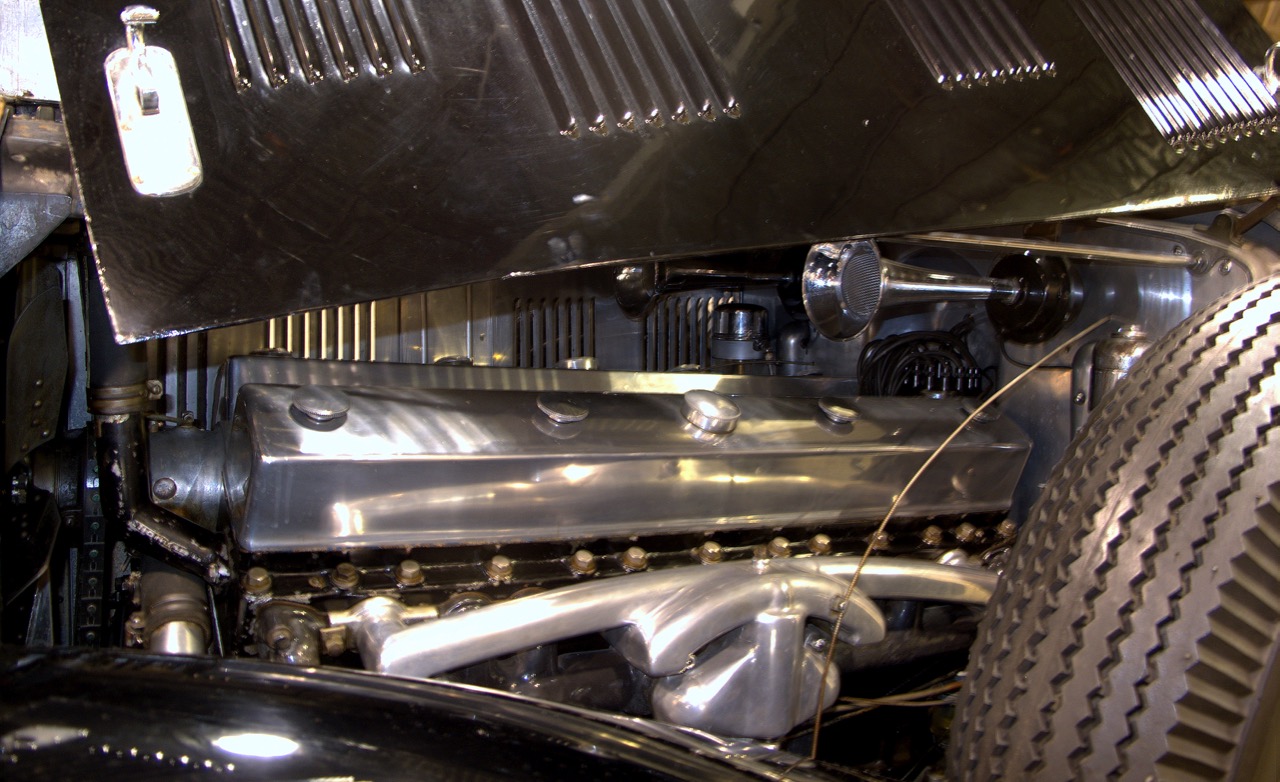

Another Depression victim was Peerless, the Cleveland-based luxury brand that had set new standards befitting its name in the 1920s, but not before it tried to match Cadillac and Marmon with a V16 of its own. Three of its 173-horsepower, 465-cubic inch engines designed by another former Marmon engineer were built in June, 1931, installed in chassis and sent to California-based Murphy for installation of aluminum bodywork.

Only one sedan (the other two were to be a coupe and a convertible) was completed before Peerless bailed out of the car business that year. The Crawford Auto-Aviation Museum displays it today and calls it the prototype for the never-built 1932 model.

This wasn’t anywhere near the end for Classic Era V16s, though. GM and Cadillac survived and thrived and kept building V16s through 1940, though the V12 proved more popular. The Series 452 was replaced by an all-new design, dubbed the Series 90 (then, as now, luxury-brand nomenclature was a fluid and confusing thing) for 1938. The angle between banks on the Series 90 was 135 degrees and dual carbs sat atop the intake manifold mounted inside this shallow V. With bore and stroke both at 3.25 inches, this square design displaced 431 cubic inches. Output, again likely conservatively stated, was 185 horsepower at 3200 rpm. It was an L-head design, though, and while 250 pounds lighter than the Series 452, its performance margin over the improving mass-market V8s was shrinking. Mostly it existed because Lincoln still had a V12 and Cadillac couldn’t retreat to an all-V-8 lineup yet, even if the sixteens were selling only a couple hundred a year.

The pretty detailing that had made the original V16 so wonderful to behold was mostly absent and what remained was buried way down in the Cadillac. The new engine sat much lower, satisfying the influential designers trying to lower the hood lines on cars, but one outcome was that it could be installed in normal production bodywork.

Gone were the days of lavish bespoke coachwork bodies. From 1938-40, about 500 were sold. All told, over a full decade (1930-1940), Cadillac built fewer than 4,440 V16 cars, but that made it the world’s biggest producer by a factor of 10. Other V-16s, mostly diesels, have seen duty in marine, aircraft and railroad applications, but they’re rare in cars. Harry Miller ran one at Indy in 1931-32,

All this was evident at the CCCA show in Novi, and there was plenty of time to wander from car to car comparing details, asking the friendly owners to open the hoods and contemplating a slower-paced pre-WWII world. There’s little wonder that Cadillac evoked this era in its 2003 Sixteen concept car, engineering an all-new V16 for it based on what was then the next-gen Corvette V8.

Other V16s, mostly diesels, have seen duty in marine, aircraft and railroad applications, but they’re rare in cars. Harry Miller ran one at Indy in 1931-32, the short-lived Cizeta-Moroder V16 ultraexotic supercar of the 1990s presaged the Bugatti Veyron (technically not a V but a W design, like V8s paired side-by-side rather than end-to-end), and there was another never-produced 21st century V16 engineered by BMW and Rolls-Royce. You can see it in a car used in Rowan Atkinson’s second spy-movie spoof, Johnny English Reborn, but frankly, we were happier sharing space with the originals on the show floor in Novi.

Photos by Kevin A. Wilson